Applause to Sharon Otterman of the New York Times for writing a candid and unbiased, description of reality in the illusory World of the DOE and the Reassigned teachers. After the signing of the flimsy Rubber Room agreement between Mike Mulgrew and Mayor Bloomberg, the public has been mislead into believing that the Rubber Rooms have been closed and that all cases are being expedited as briskly as possible. The newspapers have done nothing but scapegoat and blame teachers for the DOE's failures. Ms. Otterman accurately quoted the telephone conversation that I had with her while travelling home from 65 Court Street in Brooklyn. Unlike the reporters that I've spoken to in the past, Ms. Otterman asked questions without trying to paint a negative picture of the Reassigned teachers. For now, Ms. Otterman has restored my faith in the press and receives a rare rubber stamp for reporting the truth. To be continued...

New York Teachers Still in Idle Limbo

By SHARON OTTERMAN

Published: December 7, 2010

For her first assignment of the school year, Verona Gill, a $100,000-a-year special education teacher whom the city is trying to fire, sat around education offices in Lower Manhattan for two weeks, waiting to be told what to do.

For her second assignment, she was sent to a district office in the Bronx and told to hand out language exams to anyone who came to pick them up. Few did.

Now, Ms. Gill reports to a cubicle in Downtown Brooklyn with a broken computer and waits for it to be fixed. Periodically, her supervisor comes by to tell her she is still working on the problem. It has been this way since Oct. 8.

“I have no projects to do, so I sit there until 2:50 p.m. — that’s six hours and 50 minutes,” the official length of the teacher workday, she said. “And then I swipe out.”

When Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg closed the notorious reassignment centers known as rubber rooms this year, he and the city’s teachers’ union announced triumphantly that one of the most obvious sources of waste in the school system — $30 million a year in salaries being paid to educators caught up in the glacial legal process required to fire them — was no more.

No longer would hundreds of teachers accused of wrongdoing or incompetence, like Ms. Gill, clock in and out of trailers or windowless rooms for years, doing nothing more than snoozing or reading newspapers, griping or teaching one another tai chi. Instead, their cases would be sped up, and in the meantime they would be put to work.

While hundreds of teachers have had their cases resolved, for many of those still waiting, the definition of “work” has turned out to be a loose one. Some are now doing basic tasks, like light filing, paper-clipping, tracking down student information on a computer or using 25-foot tape measures to determine the dimensions of entire school buildings. Others sit without work in unadorned cubicles or at out-of-the-way conference tables.

“They told me to sit in a little chair in a corner and never get up and walk around,” said Hal Lanse, a $100,000-a-year teacher from Queens who had been accused of sexual harassment. He was assigned to an administrative office on Fordham Road in the Bronx in September as part of a deal that led the city to drop the charges against him.

One day he plopped down on a couch in the hallway and began reading a novel, he said. Eventually, he dozed off. Then he was asked to “paper-clip some papers” and refused: he was charged with insubordination. He is now collecting his full salary at home in Queens, with plans to retire in January; the city is trying to fire him for insubordination before then, which would reduce his pension.

“There are indeed still rubber rooms,” he said. “They just don’t call them that.”

While the teachers are supposed to be given actual work, the Department of Education still considers them unsuitable for classrooms while their cases are pending. So it has assigned them to various offices, like those overseeing facilities and food, and the external affairs office at Tweed Courthouse, the department’s headquarters.

Barbara Morgan, a schools spokeswoman, said Friday that the teachers were being as productive as possible given the temporary nature of their administrative assignments. She provided a list of tasks that some were performing, which included processing invoices, arranging schedules, answering phones and scanning documents.

Deborah Byron, 45, was one of about 60 teachers told to report to the offices of the School Construction Authority in Long Island City, Queens. On their first day, they were told they would be responsible for “collecting data,” and someone began handing out folders with lists of school names and 25-foot retractable tape measures.

The teachers fanned out to different schools to measure every classroom, auditorium, athletic field and parking lot, for precisely the contractually mandated six hours and 50 minutes each school day. They frequently interrupted classes to do their work. Sometimes custodians said, “Hey, we already have this, let us print it out for you,” and offered blueprints, Ms. Byron said. In those cases, she would do spot checks.

While other reassigned teachers said they felt ostracized and uncomfortable among their peers, hearing whispers about their “rubber room status,” Ms. Byron said she tried to look as official as possible, never revealing that she had been reassigned and was facing suspension for insubordination, she said.

“I had strappy sandals on, and a clipboard and a pen, and an old Board of Education ID,” she said. “Some of the younger teachers were almost envious — they came up and said, how did you get this job? Because they were struggling with 20-something kids and I’m here walking around.”

In October, Ms. Byron was reassigned to a truancy center in a church basement in Far Rockaway, Queens. When the police brought in truants, she looked up their records on her personal laptop and tracked down their parents’ and school phone numbers. Then she tried to counsel the students. “I talk to them and ask them why they didn’t go to school,” she said at the time.

Reassigned teachers work at a dozen truancy offices around the city, but not all of them may be as effective. Ms. Byron said the other teacher she worked with did not bring her own computer and still could not access the system by mid-November. (Ms. Byron was recently sent home, her case concluding with an eight-month unpaid suspension.)

Despite the difficulties of finding the teachers actual work, cases are moving much faster than before the April agreement, when lawyers for both sides, arbitrators and defendants all played a role in dragging them out, sometimes for years. In mid-November, there were 236 teachers and administrators still in reassignment, down from 770 when the deal to close the rubber rooms was signed.

Ms. Morgan, the city spokeswoman, said the city was on track to close all the cases that had existed before April by the end of the year, except for those involving arrests or special investigation. The city did not provide information on how many teachers were fired, suspended or fined, and how many returned to teaching, saying that information would be available in January.

Last month, 16 accused teachers were supposed to return to the classroom when officials missed a new 60-day deadline to file formal charges against them. But some got their charges as soon as the following day, and most still have “rubber room duties” in schools, said Betsy Combier, a former union employee who now counsels reassigned teachers independently.

While several former rubber room teachers said they much preferred their new, comfortable assignments, describing luxuries like office-cleaning services and microwave ovens, others said they missed the camaraderie of the rubber room. All said they would rather be back teaching students.

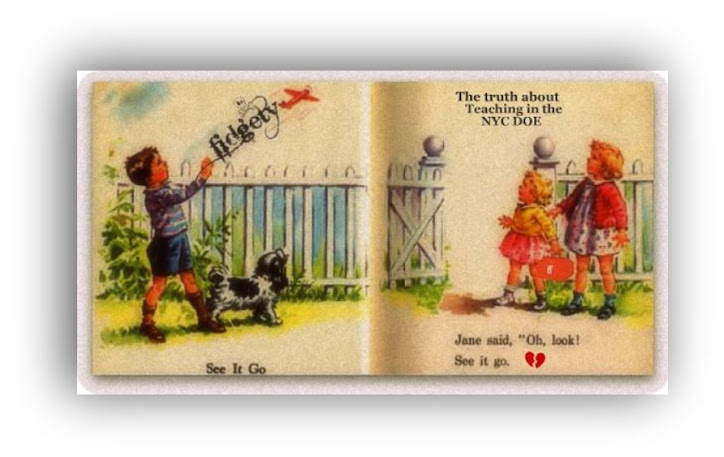

“The people from my rubber room are all here,” said a preschool teacher who blogs under the pseudonym FidgetyTeach and has been assigned to administrative offices in Downtown Brooklyn, “and we are all very distressed.” She declined to be identified by name because her case was still before an arbitrator.

She was reassigned three years ago after she was accused of leaving a child unattended. She said that while the people in her new office were pleasant enough, she had had nothing to do since the first week.

“Some people are doing filing, but they are not even wanting to do it,” she said of her fellow reassigned teachers. “It’s menial work. Most people are not doing anything; they are just sitting there. This is punishment, whether the city wants to see it that way or not.”

Juliet Linderman contributed reporting.

Link to Comments Below:

Link to Comments

2 comments:

It was an accurate report and I must congratulate you on your courage to tell the truth. We all know that the DOE has a habit of retaliating against teachers who are quoted in the papers. Just look at David Pakter's 3020-a hearing.

Thank you Chaz. I speak the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth... unlike the principals who don't know the meaning of the word. I don't think that the DOE could possibly hurt me more than they already have...Let me assure you, I have just BEGUN to speak!!

Post a Comment